Malicious actors face a difficult task in online illicit markets. How can they convince others that they are offering a high quality service (ex. selling stolen credit card numbers) without exposing themselves to arrest or providing their victims (ex. financial institutions) with enough information to prevent further victimization? This blog post investigates how malicious actors build trust. It also provides an example of a trick they use that can actually backfire on them.

Credibility Through Bold Claims and Trust Ratings

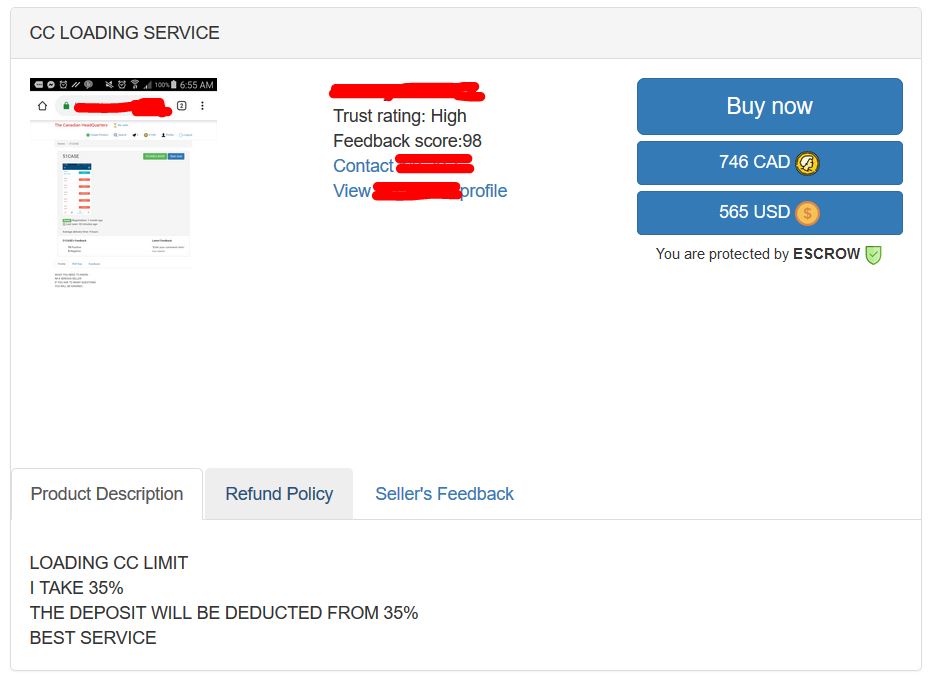

Malicious actors know that talk is cheap online. Many of them still take the time to make bold claims about their products and services. Some of these claims are very basic as seen in the Figure below. Others claim for example to have exploits that have been working for years and have been successful in victimizing tens of thousands of individuals.

Others rely on underworld authorities to build their credibility. As shown in the Figure above, the administrators of online illicit markets tag malicious actors with trust ratings. These badges increase the credibility of malicious actors. Past customers also provide the underworld with their own input through the automated feedback systems. The actor in the Figure above appears to be a credible actor based on the 98 past customers that have posted feedback.

Credibility Through Customers’ Experiences

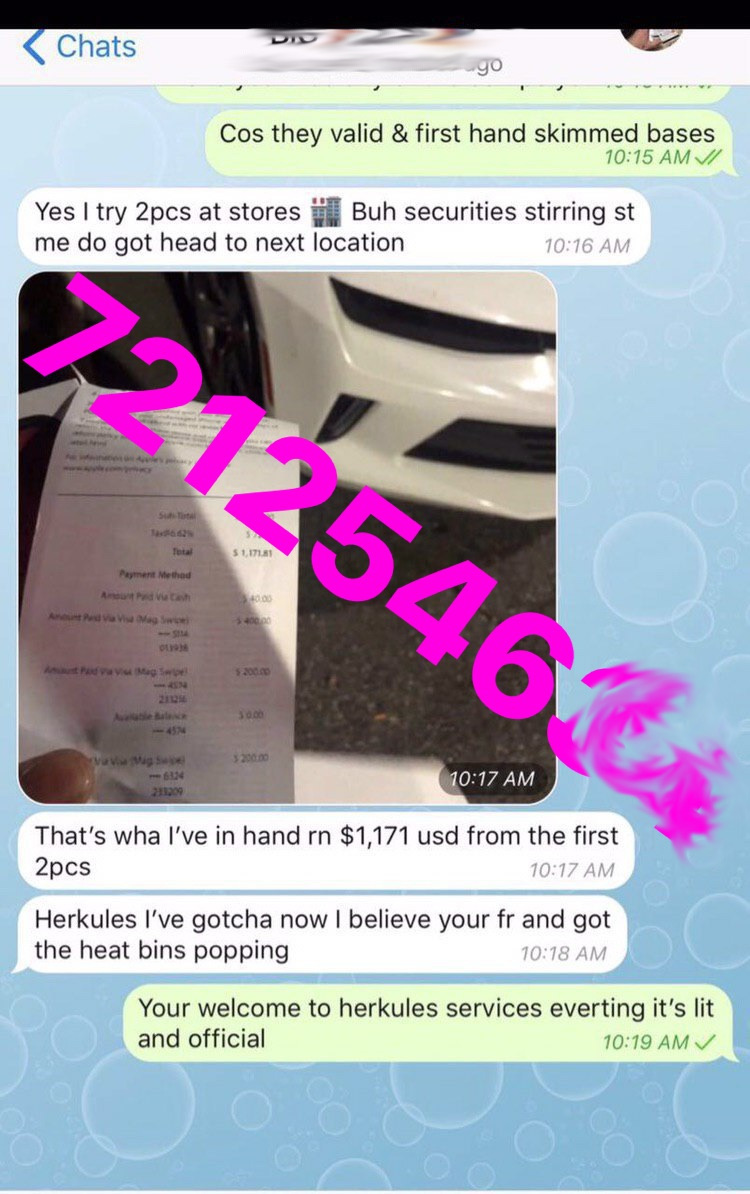

Building credibility through claims and trust ratings is the most basic and safest activity an actor can do to attract buyers. Some malicious actors go one step further and publicly share their chats with their past customers as evidence of their good service.

In the Figure above, a customer says that he first tried 2 stolen cards in a store but decided against it because of the store’s security. He later tried the cards at another store and got over US$1,100. He can be seen in the last message praising the vendor Herkules.

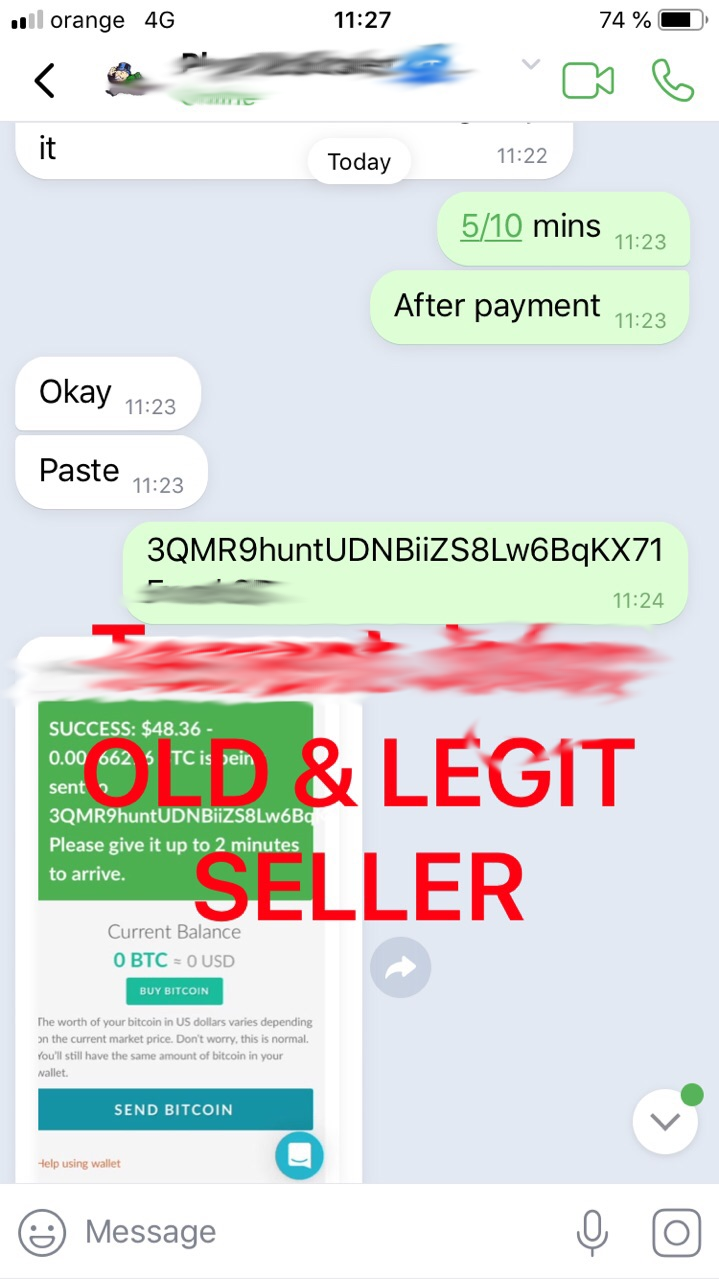

While not much can be gathered from the first chat session, the second displays a message where a malicious actor publishes their bitcoin wallet. The message also publishes a confirmation that a buyer actually purchased a service from them. Our investigations show that malicious actors regularly publish such bitcoin wallets, but that they would do better not to be so open with their information.

Tracking Bitcoin Wallets

Although seemingly of little importance, this bitcoin address can give out a lot of information. All bitcoin transactions are public and published in the bitcoin blockchain. We identified 15 bitcoin wallets tied to carders over the last two weeks and explored the blockchain to understand how these wallets were used. We found out that these tools, that are supposed to build trust, actually question the very trustworthiness of these offenders:

- 3 bitcoin wallets that were supposed to have received a payment never received a payment. The malicious actors therefore faked a conversation with a buyer to gain credibility.

- 8 bitcoin wallets had an incoming transaction, but that transaction dated back to February of 2019 or, in the worst case, to June 2015. It looks as though the malicious actors either showed an old conversation or faked their conversation and put in a (random?) bitcoin wallet.

- 4 bitcoin wallets did receive a payment in the previous weeks but the total amount received to each of these addresses is under US$250.

What it all means

This short analysis is a reminder of the true nature of malicious actors. These actors cheat and lie to gain access to stolen personal and financial information. They also do the same to each other to make sales.

The cheating nature of malicious actors may lead analysts to overestimate the true importance of some actors who make the boldest claims. The key to better intelligence is to validate the intelligence gathered using a multitude of sources. Our combined Firework and BitCluster tools allow for the tagging of bitcoin wallets as well as the characterization of malicious actors based on their revenues, for example.

In this case, our tools suggests that the actors trying the hardest to convince their peers that they have satisfied customers may actually be those that have the fewest.

Subscribe to our blog to stay up to date on the darknet and cybersecurity.